Why Musicians Can’t Sleep After Evening Performances — And How to Fix It

Food, light, and timing mistakes that keep you wired instead of recovering

PERFORMANCEHABITSHEALTH

Naama Neuman

9/7/20257 min read

When You Can’t Sleep After a Performance

You collapse into bed after a performance, exhausted — but your body refuses to follow. Your mind races, your eyes stay open, and by morning you feel like you never slept at all — fingers sluggish, tone unfocused, rehearsal feeling like climbing uphill.

For many musicians, this isn’t a one-off. It’s a cycle: play late, lie awake, drag through the next day, repeat.

My Story: Late Nights, Snacks, and Restless Sleep

For years, I thought I was just a “night owl.” Going to bed between midnight and 2 a.m. felt normal — my whole family was like that, and concerts only reinforced the habit. Even if I got 7 or 8 hours of sleep, I’d still wake up tired, and falling asleep was often a battle.

As a professional musician, that schedule felt normal because so many concerts ended late. A small dinner before the performance meant I was hungry afterward. Since I wasn’t yet eating in a way that kept me satisfied, I’d almost always snack late at night — often in front of my laptop to “wind down.”

Over time, I wasn’t just tired — I felt drained. Seasons of late concerts, bad food, and poor sleep piled up until I felt detached from the music itself. By the time a free day came, I had to force myself to pick up the flute just to prepare for the next program. The combination of the wrong diet and unmanaged sleep almost made me stop playing altogether.

It wasn’t until COVID stopped the concerts — and I changed my diet — that I noticed something different. With fewer late nights and less hunger at night, I naturally started going to bed earlier. Being in bed by 9 and waking with the sunrise opened my eyes to how much timing matters. It wasn’t only about the number of hours I slept — it was when I slept and when I ate that shaped how rested I felt.

The Role of Circadian Rhythm in Musicians’ Recovery

Your body runs on circadian rhythms — 24-hour cycles that govern nearly every system: sleep, digestion, hormones, focus, even tissue repair. Think of it as your internal conductor, keeping the orchestra of your organs and cells in sync.

Two main “timekeepers” set this rhythm:

Light resets the central clock in the brain (the suprachiasmatic nucleus). Morning sunlight tells your body it’s daytime. Evening darkness signals night. But bright stage lights at 10 p.m.? They confuse the system, telling your brain it’s still daytime.

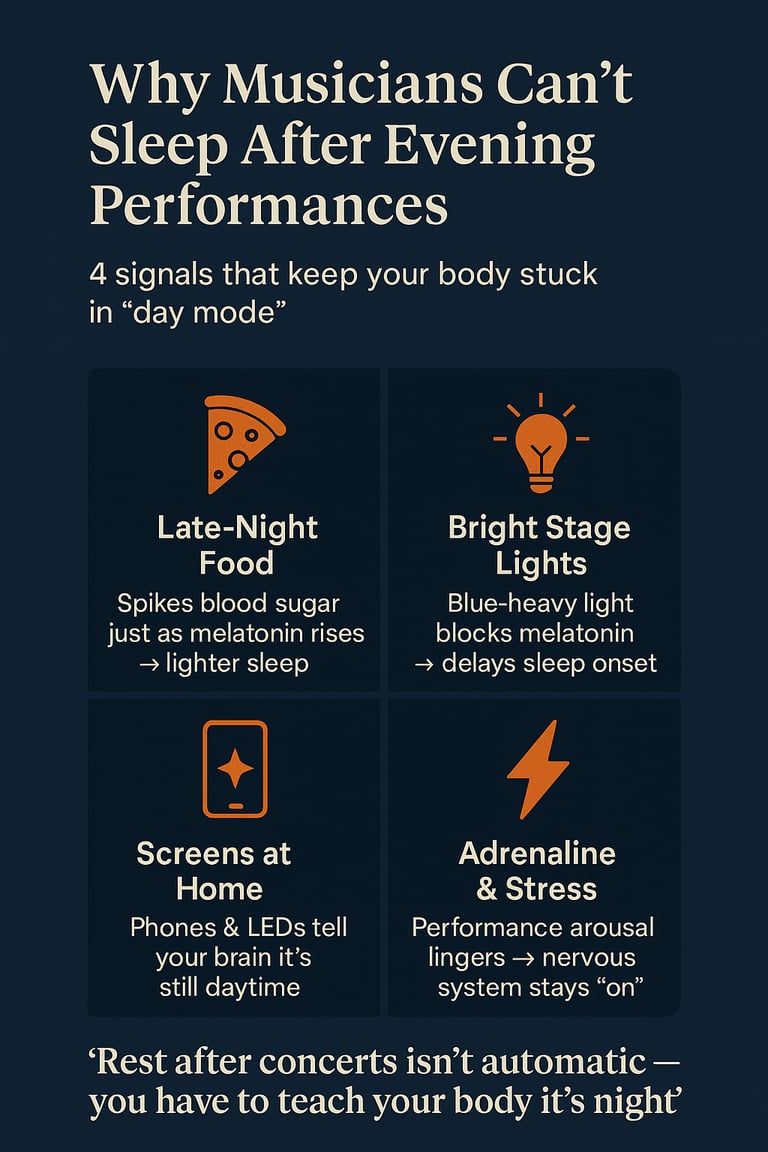

Food controls what scientists call peripheral clocks — built-in timers in organs like the liver and pancreas that dictate when to digest, release insulin, and repair. Eating late keeps those clocks running long after they should have shut down. Instead of recovery mode, your body stays in “active” mode, which makes sleep lighter and less restorative.

When these signals are out of sync — light saying “day,” food saying “keep working,” melatonin rising to say “sleep” — rest is disrupted. You may sleep, but you don’t feel restored.

As Dr. Satchin Panda puts it: “Light and food act as primary timekeepers for our internal clocks. If they’re out of sync, your recovery will be too.”

It’s like living with mild jet lag every week.

Why Musicians Should Care About Circadian Disruption

Circadian disruption isn’t just about poor sleep — it’s about performance and health. Late-night habits keep adrenaline and cortisol high, delay melatonin, and block the deep slow-wave sleep where:

The brain consolidates memory.

The body repairs tissue.

Mood is stabilized.

That means:

Finger coordination feels sloppy in morning rehearsals.

Focus drifts sooner in lessons or practice.

Recovery from tendon strain slows.

Mood turns irritable or anxious.

And it’s not only about performance. Misaligned rhythms drive systemic inflammation. Pro-inflammatory signals stay elevated, repair processes get blunted, and immunity weakens. For musicians, that means more frequent colds, slower healing from injuries, and the constant feeling of being “run down.”

In short: circadian misalignment makes you less resilient — on stage and off.

The Hidden Damage of Blue Light After Performances

Stage lighting is harsh — bright white or blue-heavy light. At night, this is the worst spectrum for your circadian clock. Blue light directly suppresses melatonin, the hormone that prepares you for sleep. Even one hour of exposure can delay melatonin release by hours.

It’s not just the stage. Many of us come home and flip on bright LED kitchen or bathroom lights, or stare into our phones. To your brain, that light is another sunrise. Modern LEDs make it worse than older, warmer incandescent bulbs, because they’re loaded with blue spectrum.

What this means: your body stays in “day mode” long after the concert, even though you’re begging for rest.

Practical Tips for Sleeping Better After Evening Performances

Even if you can’t control concert times, you can still control the signals you send your body after — and those cues make the biggest difference.

1. Fuel before the performance.

Eat a protein- and fat-rich meal 2–3 hours before stage time. Prevents hunger later and avoids sugar crashes.

Good options: eggs with cheese, salmon with buttered vegetables, steak with mushrooms.

Skip the traditional pasta dinner — it spikes blood sugar and sets you up for a crash.

2. Skip post-concert carbs (and alcohol).

Carbs spike blood sugar just as melatonin rises, delaying deep sleep. Alcohol may knock you out, but it fragments sleep and suppresses REM.

If you need something, stick with protein or fat — cheese, jerky, boiled eggs.

If you’ve got rehearsal or an audition in the morning, skip alcohol altogether.

3. Protect yourself from stage and screen light.

Bright, blue-heavy light tells your brain it’s still daytime.

Wear blue-light blocking glasses backstage.

At home, use amber lamps, incandescent bulbs, or candles for evening light.

Keep your phone out of the bedroom — even night mode tempts distraction. Use an alarm clock instead.

4. Set a recovery rhythm the next morning.

Don’t expect peak performance after a late night.

Prioritize lighter work: slow practice, technical drills, or admin.

If fatigue lingers, use a 20–30 minute nap early in the afternoon.

5. Create a post-performance ritual.

A ritual signals your body that the performance is over and it’s safe to rest.

Start on the way home. Do a short mental review — note one or two takeaways, then let it go. Or listen to calming music reserved for evenings.

Shift your environment. As soon as you arrive home, dim the lights, switch to amber or incandescent bulbs, and change into comfortable clothes.

Clear your mind. Write down tomorrow’s goals, journal briefly, or do a short meditation.

Head to bed. Aim to be in bed within 30 minutes — calm, settled, and ready for sleep.

👉 Think of this as a reverse warm-up. Each step helps your nervous system leave performance mode and enter recovery mode.

Myths That Keep Musicians Stuck

“It’s just adrenaline.”

Adrenaline plays a role, but late-night food and light confuse your body clock just as much. Repeat the cycle often enough, and shallow, restless sleep becomes your new normal.

What to do instead: Create cues that guide your body back into “night mode.”

“More sleep will fix it.”

Sleeping in doesn’t repair poor-quality sleep. What matters most is when you sleep and the signals you give your body.

What to do instead: Keep a consistent wake-up time. Use one or two short naps the next day to restore energy without pushing bedtime later.

“Coffee is the answer.”

Coffee may get you through rehearsal, but too much — or too late — worsens recovery.

What to do instead: Keep coffee early. Pair it with cream or fat for stable energy, and don’t rely on it as your only fix.

Mindset for Musicians: Learning to Recover Like You Practice

We’ve all stumbled into a morning rehearsal after a late concert, wondering if we’re just not cut out for mornings. It feels normal — but “normal” isn’t the same as healthy.

The truth is, most of us never learn how to come down after a performance. We train scales, endurance, even stage nerves — but almost no one trains recovery. Adrenaline, light, and late eating keep the nervous system on high alert long after the concert ends.

Here’s the good news: recovery can be trained the same way performance is trained. A consistent post-performance ritual works like a warm-up in reverse. It tells your body the concert is over and it’s safe to switch off.

Just as you wouldn’t expect your fingers to play perfectly without practice, you can’t expect your sleep and focus to recover without clear signals. With small, repeated steps, your system learns to downshift. Over time, sleep deepens, mornings feel lighter, and the cycle of exhaustion breaks.

In Conclusion

Concert nights will always run late, and adrenaline will always be part of performing. But lying awake for hours and dragging through the next day doesn’t have to be the norm.

Post-performance recovery isn’t automatic — it’s something you can train. By fueling before instead of after, dimming the lights, and repeating a simple ritual, you guide your body from stage mode into sleep mode.

The payoff: deeper rest, steadier focus, and mornings that don’t feel like punishment for doing your job.

So the next time you walk off stage, ask yourself: Am I helping my body recover, or keeping it stuck in performance mode?

👉 Want more musician-focused strategies like this? Subscribe to The Focused Musician and join others learning how food, light, and recovery shape performance.

📚 Research Notes

Late Eating & Circadian Rhythm

Lopez-Minguez J, Saxena R, Garaulet M, Scheer FAJL (2018) — Late dinner impairs glucose tolerance in MTNR1B risk allele carriers.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5634913/

→ Late dinners disrupt glucose control, especially in those with genetic risk.Garaulet M, Gomez-Abellan P, Saxena R, Scheer FAJL (2022) — Interplay of Dinner Timing and MTNR1B Type 2 Diabetes Risk Allele in Glucose Control.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8918262/

→ Dinner timing directly affects blood sugar regulation.

Light & Sleep

Chang A-M, Aeschbach D, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA (2015) — Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25535358/

→ Evening blue light delays sleep and reduces morning performance.Shechter A, Kim EW, St-Onge M-P, Westwood AJ (2017) — Blocking nocturnal blue light for insomnia: A randomized controlled trial.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5703049/

→ Blue-light blockers improve sleep in those with insomnia.

Meal Timing & Recovery

Qian J, Scheer FAJL (2016) — Circadian System and Glucose Metabolism: Implications for Physiology and Disease.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4842150/

→ Circadian timing strongly influences glucose control and recovery.Wilkinson MJ, Manoogian ENC, Zadourian A, et al. (2019) — Ten-Hour Time-Restricted Eating Reduces Weight, Blood Pressure, and Atherogenic Lipids. (Satchin Panda, senior author)

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6953486/

→ Time-restricted eating improves metabolic health markers.

Alcohol & Melatonin

Rupp TL, Acebo C, Seifer R, Carskadon MA (2007) — Effects of moderate alcohol ingestion on the melatonin rhythm in human volunteers.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17612945/

→ Alcohol suppresses melatonin and disrupts circadian rhythm.