The Vegan Lie That’s Trapping Young Musicians

Before you choose vegan for ethics or health, here’s what you should know.

NUTRITIONPERFORMANCEHEALTHETHICS

Naama Neuman

10/12/20258 min read

If you’re thinking about going vegan, you’re not alone. Many young musicians do — to feel healthier, to live ethically, to align with what everyone around them seems to believe. But the truth is harder: veganism doesn’t protect your health, it doesn’t protect animals, and it doesn’t protect the planet.

What begins as a noble choice often becomes a trap — draining the very focus, stamina, and resilience musicians depend on.

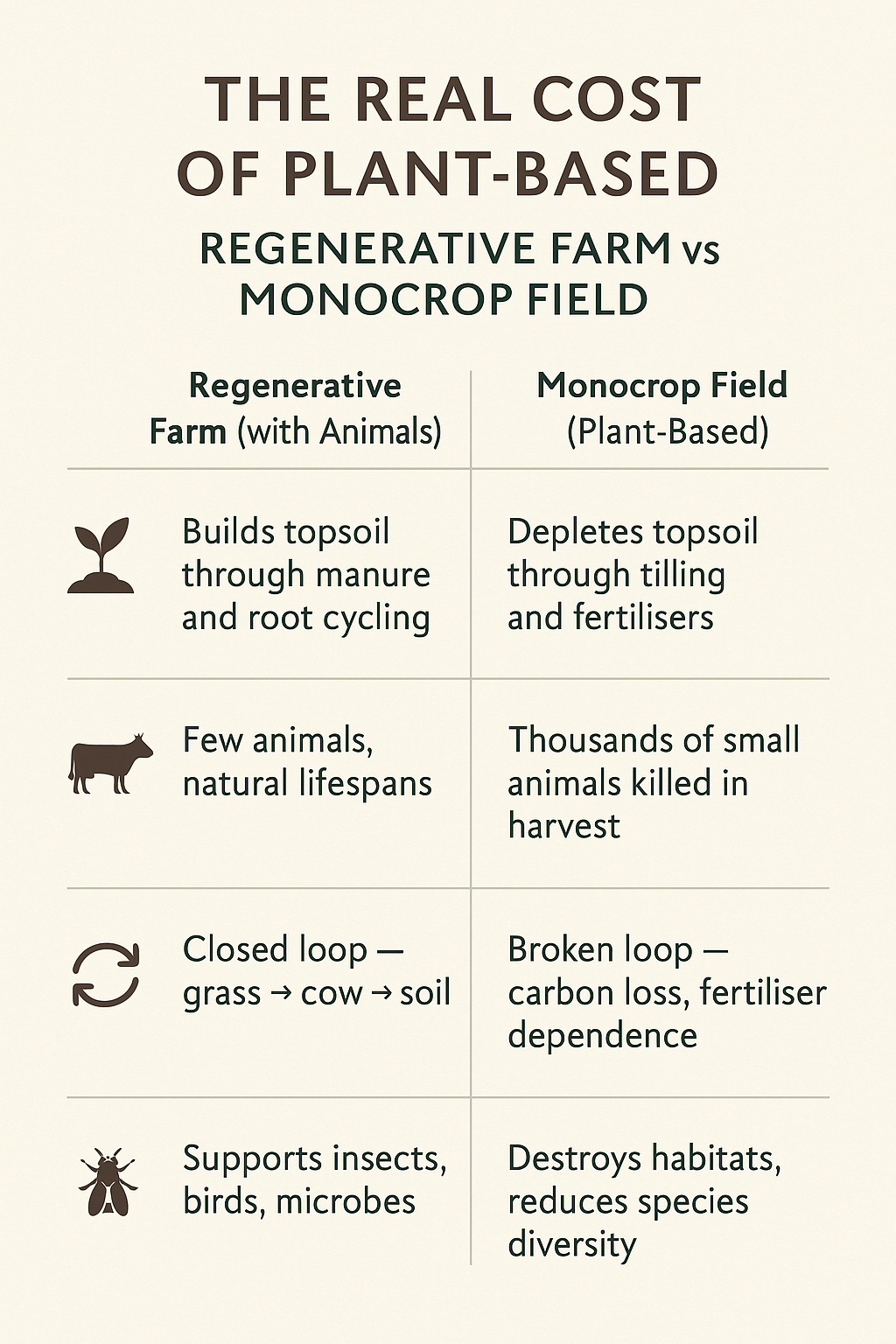

The Ethics Trap — Why “No Harm” Isn’t True

Veganism is marketed as a way to cause no harm. But harm happens in two directions: to your body, and to the land.

Vast monocrop fields of soy or wheat don’t exist in nature — they are forced into being by machines and chemicals. To create them, everything else is cleared or killed: mice, birds, insects, even the microbial life that keeps soil alive. Calling this “bloodless” food is a lie.

By contrast, ruminant animals — cows, sheep, bison — sustain ecosystems. Their grazing cycles nutrients back into the ground, their manure feeds soil microbes, and their presence supports biodiversity. Humans are animals too, and like other carnivores, our role in that cycle is to eat other animals. Break that link, and both land and people begin to weaken.

Ethics isn’t about avoiding death; it’s about how life continues. True ethics means supporting small farms that care for their animals and their soil — not the industrial systems that strip both bare.

The Health Trap — Why the Glow Doesn’t Last

Veganism often feels good at first. Cut out processed junk, and you’ll notice lighter digestion, clearer skin, maybe more energy. But that early glow isn’t from plants — it’s from removing industrial foods. The trap is that deficiencies begin immediately, even if you don’t feel them yet.

Your body has stores of B12, iron, and other key nutrients. They mask the damage for a while — usually three to five years. By the time the tank runs empty, most people can’t believe the same diet that once made them feel better is now leaving them exhausted and fragile.

For undergraduate students, that delay means something specific: by the time you finish your degree, those hidden deficiencies start to surface. You graduate with less energy, poorer concentration, and higher anxiety — symptoms easily mistaken for “post-university stress” or the pressure of starting professional life. In reality, it’s your nutrient reserves running out.

The common breakdown:

Nutrient gaps: B12, iron, zinc, taurine, DHA/EPA, creatine — all critical for nerve stability, mood, and stamina — decline steadily.

High carb load: grains, beans, oat milk, and starch-heavy staples keep insulin high. The result isn’t just slow weight gain, but brain fog, anxiety, adult acne, and eventually insulin resistance or even diabetes.

Protein quality gap: plant proteins don’t repair muscle or tendons the way animal proteins do. Recovery slows, hunger never stops, and lean mass erodes.

For musicians and athletes alike, the consequences are the same: slower recovery, weaker performance, and emotional volatility that training or practice alone can’t fix. The health trap is cruel — the diet that first feels like an upgrade quietly drains the body of what it needs most to thrive.

The Performance Trap — When Focus and Stamina Collapse

For a while, you might convince yourself things are fine. You’re eating “clean,” your conscience feels lighter, and the early glow hasn’t worn off yet. But behind the scenes, your body is running on empty — and musicians are often the first to feel it.

Without steady animal protein and fat, the breakdown shows up where it hurts most:

Muscles and tendons don’t repair efficiently — aches linger, injuries heal slowly.

Hormones destabilise — for women, menstrual pain and pre-period mood swings intensify; for men, testosterone drops, bringing less energy, lower sex drive, and faster balding.

Insulin stays high from constant grazing — keeping your nervous system on edge and your focus unstable.

On stage and in the practice room, it feels like this: overthinking every passage, anxiety that builds instead of settles, nights of poor sleep, mornings of exhaustion, tremors, restlessness, and longer learning curves for new pieces. It isn’t age or pressure — it’s poor fuel.

This is what happens when the brain runs only on glucose: it inflames easily, tires quickly, and fails to consolidate memory. For performers, that means every note costs more effort than it should.

The Planet Trap — How Veganism Backfires on the Environment

Veganism is sold as the diet that will save the planet: fewer cows, less methane, less damage. But the reality is the opposite.

Methane isn’t the enemy. In a healthy system, methane from cows is part of the carbon cycle. Grass pulls carbon from the air, ruminants eat the grass, and their manure and methane return nutrients to the soil. Remove the animals, and the loop breaks — carbon balance fails, soil fertility collapses, and synthetic fertilisers take over.

How much carbon are we talking about? Today, carbon dioxide makes up only 0.04% of the atmosphere (~420 ppm). That’s all — a trace gas, yet it’s the primary food for plants. No carbon, no plants. No plants, no animals.

In the past, levels were far higher — and life thrived because of it:

Cambrian (~500 million years ago): 4,000–5,000 ppm — marine life and the first complex plants exploded.

Jurassic (~200 million years ago): 1,800–2,000 ppm — lush forests supported dinosaurs and large mammals.

Cretaceous (~100 million years ago): 1,000–1,500 ppm — warm, wet, and densely vegetated.

Farmers still use this principle: greenhouses enrich the air with 1,200–1,500 ppm CO₂because it accelerates plant growth. That’s why it’s called a “greenhouse gas.”

Where does most CO₂ come from? Not cows — and not mainly humans. The largest source is the oceans, which release stored carbon as they warm — a natural cycle driven primarily by heat from the Earth’s core, not by human activity, and one that has operated for millions of years.

The soil crisis. Modern monocropping — soy, corn, wheat — strips topsoil at a staggering rate. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization warned in 2014 that if current practices continue, global topsoil could be gone in 60 years; other scientists estimate closer to 30 years in intensively farmed regions. Without topsoil, there is no food system at all.

Plants are already weaker. Studies comparing modern crops to samples from the 1940s–50s show steep mineral declines — less iron, magnesium, and zinc. The “nutrient-rich plants” promoted in vegan diets simply don’t deliver what they once did.

The planet trap: The diet marketed as sustainable accelerates the destruction of soil, carbon balance, and nutrient density. Real ecological repair comes not from removing animals, but from putting them back where they belong — on the land, cycling life.

The Information Trap — The Science That Isn’t Science

Most of the “evidence” used to promote veganism comes from food-frequency questionnaires — surveys where people tick boxes about what they ate last month, and researchers try to link those answers to health outcomes. These studies show associations, never cause and effect, yet they’re treated as proof.

The distortions start immediately:

Who funds it? Governments and industries that profit from cheap grains, soy, and processed foods.

What counts as ‘meat’? A pizza with pepperoni or a burger meal is logged as “meat,” even though most calories come from bread, fries, and seed oils. When problems appear, meat takes the blame.

Who eats what? Wealthier, health-conscious people eat more vegetables and whole grains but also exercise more, smoke less, and access healthcare sooner. Their better health is credited to plants, not lifestyle.

If a nutrition headline says a food “causes” or “prevents” disease, it’s false.

Controlled lifetime diet studies are unethical and impossible. What we have are surveys — useful for marketing, never for proof.

The last time food research approached real rigor was in the 1960s–70s, when controlled trials on seed oils showed increased rates of heart disease and overall mortality. Those findings were buried, and modern nutrition science has relied on weaker designs ever since.

The Evolution Trap — What Human History Really Shows

The vegan story says humans are natural plant-eaters. But archaeology, biology, and history all tell a different story.

Myth 1: Early humans lived on plants.

Reality: Stone tools and butchered animal bones show humans were eating meat at least 2 million years ago, long before agriculture (~10,000 years ago). Stable-isotope studies of Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens reveal diets as carnivorous as wolves. During this period, brain size expanded from about 450 cc (Homo habilis) to 1,500 cc (Homo sapiens) — growth fuelled by meat and fat. When farming arrived, humans became shorter, brains shrank by ~10%, and disease increased. Ancient Egyptian mummies — heavy consumers of bread and beer — already show obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

Myth 2: We evolved from monkeys, so fibre must be our fuel.

Reality: Apes survive on fibre; humans do not. Great apes have large colons and cecums to ferment plants into calories. Humans lost that system. Our cecum is tiny, intestines short, and stomach acid extremely strong (pH ~1.5) — closer to vultures (~1.0) than cows (~6–7). That acidity evolved when early humans scavenged meat from predator kills. As we developed tools and hunting strategies, we became active carnivores — but the acid system remained.

Myth 3: Plants today are the same as what humans evolved with.

Reality: Ancient plants were seasonal, fibrous, and low in sugar. Modern ones are bred to be sweeter, starchier, and available year-round. Bananas once had large seeds, apples were small and tart, carrots thin and woody. Some vegetables — broccoli, cauliflower, kale, cabbage, Brussels sprouts — didn’t exist at all until recently; all were bred from the mustard plant (Brassica oleracea). They are modern inventions, not ancient foods.

The trap: Ignore this evidence, and you end up believing the human body can thrive on soy milk, grains, and engineered fruit. But every line of biology — from our brain growth to our stomach acid — shows we are built around animal foods.

Voices from Experience — When the Body Tells the Truth

This isn’t just theory. Many who’ve lived veganism long-term describe the same pattern: short-term glow, followed by decline.

Bella Ma (“Steak & Butter Gal”) — A Juilliard-trained pianist who spent years vegan for health and ethics. She later reported losing her menstrual cycle, worsening skin conditions, and constant brain fog. After moving to an animal-based diet centred on meat and butter, she describes major improvements: skin healing, energy returning, hormonal stability, and sharper mental focus.

Lierre Keith, The Vegetarian Myth — A committed vegan for 20 years, Keith documented severe health collapse — spinal damage, reproductive problems, and ecological disillusionment — before returning to animal foods.

Ex-vegan accounts: Most describe two to five years of “feeling amazing,” followed by fatigue, anxiety, injuries that don’t heal, and digestive breakdown. Once they return to animal foods, focus, stamina, and emotional stability return.

These voices reveal the same cycle: what begins as health and ethics often ends in fragility and collapse.

Conclusion — Don’t Step Into the Trap

Veganism is sold as clean, ethical, and planet-saving. But across every angle — ethics, health, performance, environment, evidence, and evolution — the story collapses.

It doesn’t spare animals; monocrop farming kills more than most people realise.

It doesn’t protect health; deficiencies begin immediately and surface as fatigue, anxiety, and poor recovery.

It doesn’t support performance; it undermines the calm focus and stamina musicians need most.

It doesn’t save the planet; it accelerates soil collapse, nutrient loss, and carbon imbalance.

It isn’t backed by strong science; only by weak surveys and industry spin.

It isn’t natural for humans; our biology shows we are built for animal foods, not soy and engineered fruit.

Ex-vegans — from authors like Lierre Keith to Juilliard-trained pianist Bella Ma — show the same cycle: a few years of glow, followed by breakdown, and finally the return to animal foods to restore health.

The choice is yours: Do you want to build a career on fragile fuel, or on the foods that powered humans for millennia — and made us the top of the food chain?